As we advance in knowledge of the Iberian language , it has been possible to define how it sounds.

If we make a quantitative analysis of absolute values based on texts of all chronologies and territories , we can perform a statistical distribution of sounds that has allowed us to imagine how the Iberian language would sound.

The sound distribution of the Iberian language is very anterior. When they spoke , the Iberians preferred the articulation located in front of the speech organs and required the obstruction of the air made with the lips , teeth and palate . The support vowel was mostly the /i/.

The surprise is that the consonant distribution is very regular, which would define the unity of language in all territories. In contrast, the vowel distribution is much less regular and presents notable differences between territories. Let us see below:

|

Askos with Iberian inscription |

Vowels:

a, e, i, o, uAlthough five vowels is the inventory generally accepted, in some texts there are distinct signs that could suggest a wider inventory. Some believe that the Iberians had a sixth palatal vowel, located between /e/ and /i/, although some researchers interpret it as a nasal or velarized vowel supported by an /a/ vowel.

The vowel most present in the Iberian, the most constant in all time and territories, is /i/. It is followed by the /e/ and then the /a/. A distance away, it is followed by the /u/ and finally the /o/. The majority distribution of palatal vowels is one of the characteristics of Iberian and not usual. Normally, languages prefer a more contrasted vowel distribution (ie AIO).

Below we summarize by zones:

Zone B, southern France. In Enserune MLH B.1.37 probably we have seven vowels. There is a double spike character interpreted as a variant of /e/ and two different spellings for the vowel /a/ (Untermann a1 and a6). In Pech Maho MLH B.7.35, however, despite being a long text composed of 44 signs, there is NOT a single isolated /a/ (value /a/ appears clearly in syllabic characters).

Zone C, Catalan coast. In Empúries MLH C.1.1, C.1.2, C.1.3, C.1.4 vowel /i/ is still the most common followed by two more variants of the vowel /a/. In Ullastret, lead, MLH C.2.3, the /a/ beats /i/. Palamos, lead, MLH C.4.1, the letter /o/ appears more than the /u/.

Zone D, central Catalonia. In Joncosa MLH D.18.1, the vowels /i/ and /e/ are very evenly matched. Considering the total distribution and adding the syllabic characters, ie /a/ + /BA/ + /TA/ + /KA/, the /e/ + /BE/ + /TE/ + /KE/ and the /i/ + /BI/ + /TI / + /KI/ give us a total of 60 (core vowel /a/), 67 (core vowel /e/) and 54 (nucleus vowel /i/) ie, the presence of the vowel /e/ exceeds that of /i/.

Zone F, Valencian coast between the river Ebre and Xúquer. In Castellon Valley Uxó, vowel distribution is very regular. The order is vowel /i/, /a/, /e/, and far away, /u/ and /o/. In Llívia and Yatoba, the distribution is very similar to the above but in Llíria, /a/ exceeds /i/, inverting the total absolute values.

We see that the differences are considerable so we believe that the issue of the vowels can still deserve some surprises. There could be other reasons? Yes. We believe that some suffixes had the grammatical mark function precisely on the consonant and, therefore, it was possible to represent it as KA, KE or KI without the need that the character had a real vowel value but only consonant one...

Consonants:

We have grouped the consonants by the articulation mode:

Plosive consonants: if we consider the entire inventory of sounds and make a quantitative analysis, the plosive occupy about 50%, ie half of the Iberian language consonant sounds are of plosive articulation.

There are still difficulties in establishing an accurate inventory of plosive sounds. On one hand, the Iberian writing used for the plosive ones, syllabic characters that join the plosive consonant to a vowel, ie, there is a single character for each of the syllables KA, KE, KI, KO, KU.

Some researchers considered that the Iberian writing was deficient because they often had no distinction between voiced and unvoiced plosives. However, new research is showing that the variability of syllabic characters is not random, authors differentiate in the same text different sounds by adding a dash more to a character. It is still unknown if this differentiation of plosives wants to represent the opposition between voiceless and voiced consonants or a place of articulation more palatalized. In fact, it could even be that it doesn't represent a place of articulation, but a mode, for example a fricative sound with an alveolar or palatal consonant cluster. In reality it is not known for real what phonetic differentiation is being represented, we only know there is a differentiation which is present in the Iberian script.

We believe that we must take into account the articulatory context, because even nowadays we still apply a law that makes unvoiced the plosive sounds at the end of the word and makes voiced them in intervocalic position. Other reasons may be the sound elisions in contact; distinction of affricated double sounds (/ts/, /dz/, /tf/, /dz/), or as explained in analyzing vowel diversity: it could be that the grammatical mark fell on the consonant. However, the plosive distribution is overwhelming and always represents at least 50% of the total consonant sounds register.

Vibrant consonants: is the second group in presence and occupy about 20% of consonant sounds. At all times and territories, there are clearly represented two different rhotic sounds interpreted as a single R and a double RR.

Fricative consonants: the third group in presence and represents approximately 13%. In Iberian there are, very clearly at all times and territories, two sibilant usually interpreted as voiced S and unvoiced Z sounds. We believe that the Iberian language also had the affricated sounds that we encounter in both the Romance languages built over their own substrate and also the Basque one.

Nasal consonants: as a consonant group represent between 6 and 7% with a distribution parallel to the one of the lateral consonants. Despite there are three different nasals accepted, unquestionably the most present is the dental nasal N. The presence of M increases in Celtiberian areas. Some of the characters accepted as nasal present interpretation problems. Their occurrence, in contexts which are preceded or followed by other consonants, seems to require that their pronunciation must be supported by a core vowel. There are cases, such as the MLH Joncosa D.18.1, with the character V (m1 Untermann interpreted as nasal) or the Valley of Uxó MLH MLH F.9.5 and F.9.7 with the character Y (m2 Untermann also interpreted as nasal) that, not only destroy the statistics but also they appear in contexts where a nasal consonant is unpronounceable. We shall therefore review these interpretations.

Lateral consonants: represent between 6 and 7% with a distribution parallel to the group of nasal consonants. In some texts we can find characters that some researchers have interpreted as a variant of the lateral. It could be a lateral palatal LL or dental LT.

So we have that N and L sum up the same as the S / Z ones, and we still have to add the R so as to, all these groups together, can equate that of the plosive consonants.

Significant absences:

Sometimes we can gather more information on what we miss than on what we can find in a language. The Iberian language has some absences that must be significant:As there remains undetermined characters, this discussion must be viewed as a first approximation as how the Iberian language could sound.

You can download a study made by Carme J. Huertas, based in the absolute frequency of the characters in different times and territories. It has been considered only the longest scripts avoiding repetitive marks and possibly numeral signs.

Download PDFProfessor Rodríguez Ramos website, in Spanish La Lengua Íbera: en Busca del Paradigma Perdido

Institut d'Estudis Ibers www.ibers.org

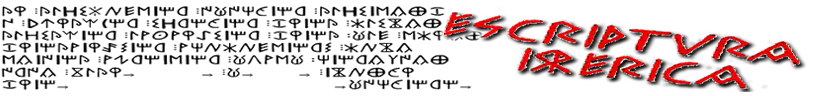

Promotora Española de Lingüística (PROEL) Alfabeto Ibérico

|

|

|

Webmistress: Núria Delgado.